Breon O’Casey, who died last year, never courted or followed fashion, but rather turned his back on it. Throughout the 60s and early 70s he was part of the complicated jigsaw puzzle picture that was the St Ives school, but then he cut himself off, getting out in 1975 just as the dealers and art historians were beginning on the forensic process of cataloguing, pricing and documenting the scene there.

O’Casey’s painting studio, 1970s, copyright estate of Breon O’Casey.

He was first ‘apprenticed’ to Barbara Hepworth’s ex assistant the sculptor Dennis Mitchell, and then joined Hepworth a couple of years later. For two or three days a week from 1959- 62 while Hepworth was making large public commissions such as her monumental ‘Single Form’ for the United Nations Building in New York, O’Casey worked as one of her studio assistants and carvers.

Breon O’Casey in 2006, (copyright www.antonycrolla.com )

Painting studio with O’Casey’s bust by Elizabeth Frink, 2011.

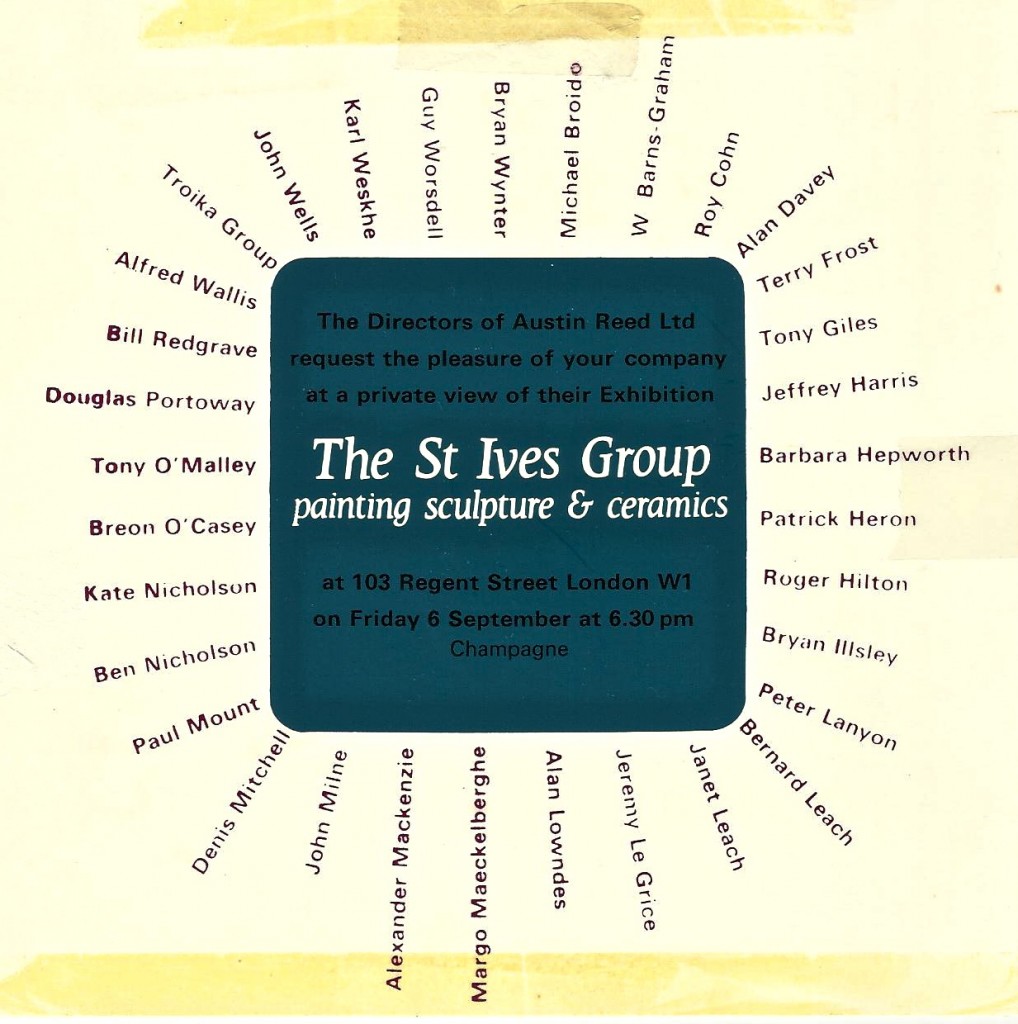

He sold an early painting, ‘Seascape,’ to his old employer Hepworth and at one of the Penwith’s shows in 1967 Jim Ede ( who had recently founded Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge) bought another. Next year another of his small abstracts was included in the ‘St Ives Group ‘ London show with works by Nicholson and Hepworth, John Wells, Peter Lanyon and Roger Hilton.

From ’67 he was vice-chairman of St. Ives’s Penwith Society of Arts, organising shows and hanging committees, setting up a print workshopand cajoling for funds. His height and steady temper came in useful when Roger Hilton – ‘a difficult bugger’ – started kicking the paintings, ‘ and we’d have to throw him out. He used to kick you in the shins.’

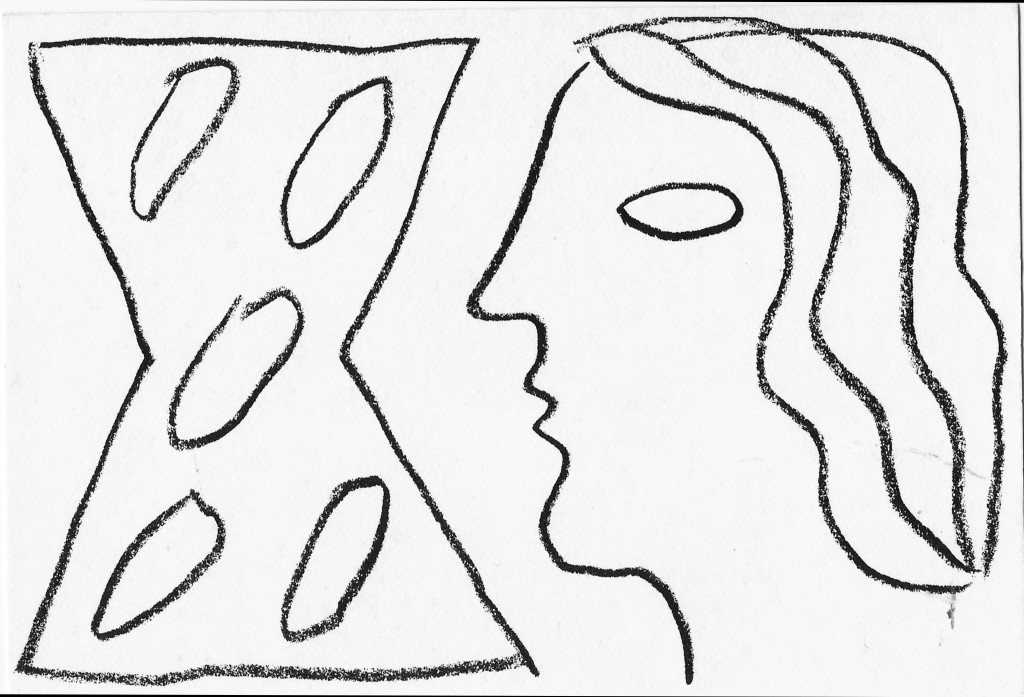

Then in the mid 70s O’Casey resigned from the Penwith and moved out of St Ives. Like Rose and Roger Hilton, Bryan Wynter and Karl Weschke he joined an artistic diaspora who found more remote places in which to work and live a dozen or so miles away. settling in Paul, midway between Penzance and St Ives. Here his painting became more assured with certain motifs recurring – the single form on a divided ground and a distinctive double ended anvil shape.

He thought the imperatives of the art market, where every work of importance must innovate or start a new fashion, a bit ridiculous, ‘Sir William Nicholson and Piet Mondrian were born in the same year. Mondrian’s work was avant garde but Nicholson was an equally good painter. Good work goes on behind the cutting edge,’ he used to say, equably.

https://www.breon-ocasey.co.uk/

Dressser and kitchen in O’Casey’s farmhouse with pottery by William and Andrew Marshall, Richard Batterham and Michael Cardew.

https://www.breon-ocasey.co.uk/

www.stonemanpublications.co.uk

[All images : copyright bibleofbritishtaste.com / estate of Breon O’Casey / Antony Crolla]

</a

</a

I loved your blog and I’m sorry to be pedantic but some of the pottery on the dresser is by Richard Batterham (rather than Batterhouse), surely? He is a really wonderful potter, a family friend and lives and works in North Dorset. David Mellor sells his work or used to.

You are absolutely right thanks so much for pointing it out.